"Enemies on our building and all surrounding buildings."

Warfare, dir. Alex Garland and Ray Mendoza 2025, 95 minutes.

I don’t even know where to begin writing about Warfare. I’ve been sitting here, plugging away for an hour now, and whenever I hit a hundred or so words I just delete it all and go back to staring at the white vastness of the unwritten review. Warfare has me stumped. It’s not that I didn’t enjoy the film, because I very much did, and it’s not like I absolutely hated the film, because I absolutely didn’t. I think it’s rather that what I’m feeling is a total ambivalence, a muted numbness - the particular feeling that I didn’t necessarily experience this in the way it feels like its creators wanted me to.

To cut through the noise: Warfare is one of the most spectacularly unmoving films I’ve ever watched. From the back of the Mockingbird Cinema I could see a myriad array of reactions ranging from disgust to exhilaration. So why did I feel absolutely nothing at all? Throughout the second half I could see almost the entire room averting its eyes from some of the most graphic injury detail I’ve ever seen in a film, or wincing with every shot fired. But I felt like I was in a museum or installation: respectfully admiring the film but from a zone of complete emotional detachment.

Warfare is the anthesis of cinema. It’s a film with an empty space where its heart should be - and make no mistake, this is part of the blueprint. Garland, working here with Iraq war veteran Ray Mendoza as co-director, has decided to make the inexplicable decision to present 90-minutes of pure, unmediated combat. Save a brief prologue, the film unfurls in a relatively consistent real-time, following a group of soldiers on a routine surveillance mission which, in a matter of minutes, descends into sheer hell when a grenade plops through a window. FUBAR, indeed. Garland and Mendoza eschew all the trappings of a quintessential, narrative cinema: what dialogue we can hear is mostly just military numberwangs or inaudible. The characters have names but rank and designation are what matter most. The events the film depicts are based on one specific incident, but there’s a grim universality here: this could be happening anywhere in the Middle-East at any given moment. It doesn’t matter where, but rather how and to who. All of this is based on memory, the film stresses to us, repeatedly. And Garland whacks out the pretentious typewriter font from Civil War so you know he means business.

What we’re seeing here, then, is an attempt to de-aestheticise military combat, to untether it from any political or ideological moorings. To let the violence and intensity speak for themselves. What a strange film this is. Garland and Mendoza have clearly watched Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest, and they clearly liked what they saw. The first section of the film shows, with unwavering determination, the deadening tedium of military routine: cleaning your gun, rationing your water, writing down numbers in a little notebook that a voice on the radio calls out. Imagine Jeanne Dielman with machine gun hunks and you’ve got a pretty clear idea of the aesthetic framework that Garland and Mendoza are situating themselves within.

Here is combat as it’s supposedly experienced, unvarnished and raw. Garland and Mendoza lift an expressionistic touch directly from Glazer by occasionally depicting the horrors of Warfare from the perspective of a drone: just as things are about to - God forbid! - get too involving, we see the world in a harsh monochrome, the characters scurrying about on the ground like ants. Strange noises in the background gradually reveal themselves to be the eerily ambivalent, drolly businesslike observations of whoever is piloting the drone.

But these sequences do little to punctuate what is effectively a 90-minute avalanche of pandemonium, without any meaningful narrative structure or development. It hits a ceiling of intensity incredibly quickly and - dare I say - ultimately winds up feeling faintly tedious by its conclusion. I respected Warfare more than I enjoyed it, and understood the angle it was trying to take, but felt absolutely nothing. Perhaps the desensitisation is the point: when one of the soldiers, Sam (Joseph Quinn) has a bomb go off directly under his feet, his legs lie at grim angles and he screams, almost continually, for the rest of the film. You get used to it. One man’s desperate attempts to cling to life melt, far too quickly, into the relentless background ambiance of sheer Hell.

That typewrite font: Garland - to be honest, I do wonder exactly what input Mendoza had here. I like to imagine him just being stood there in sunglasses, a muscle-tee and cargo shorts wondering how the camera works - uses the same annoying typewriter font as in Civil War here as well. He clearly thinks that he’s doing something important, lending an air of cool objectivity to what is fundamentally subjective, doing us all a public service. THIS IS NOT PROPAGANDA!!!! he shouts at us. But at least propaganda says something, it’s at least expressing something about the world, and even if those expressions are outright mistruths they at the very least say something about their author/s.

Films like Zero Dark Thirty or American Sniper might be misguided and flawed but they attempt to express some kind of opinion. Bigelow’s film reckons with the role of torture in the hunt for the Big Bad Wolf, and shows the moral dehumanisation of the CIA operatives hunting for him. And people shit on American Sniper because it’s made by Clint Eastwood but the clue’s in the name: the US military-industrial complex turned Chris Kyle into a killer, and when it was done with him left him to fend for himself. The Middle East, the film posits, was a straight-up meat grinder. I watched the film recently and was incredibly moved by it; I don’t know how anyone could leave that film thinking it’s remotely pro-war.

I don’t have the faintest idea what we’re supposed to take away from Warfare. That guns are heavy? The having your legs sit perpendicular to your torso might be painful? Well, yes. The film’s stubborn refusal to comment on the machinery of war and to simply depict combat as it is fought means it’s ultimately a hollow and futile exercise in ambivalence.

That is, until the credits.

I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. For some reason - and this is clearly where Mendoza’s involvement lay - the end credits of the film are accompanied by a bizarre, tone-deaf ‘making of’ short, in which we see the actors from the film juxtaposed with their real-life counterparts, many of whom have their faces blurred because of ongoing security concerns, while ambient R&B plays. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. In one case, we even see handheld, home-video footage of Cosmo Jarvis high-fiving and joking around with the wheelchair-using veteran his character was clearly based upon. Elsewhere we see the cast being taught how to hold their guns, whilst Mendoza demonstrates how they should avoid stepping on the props of severed limbs. What the fuck?

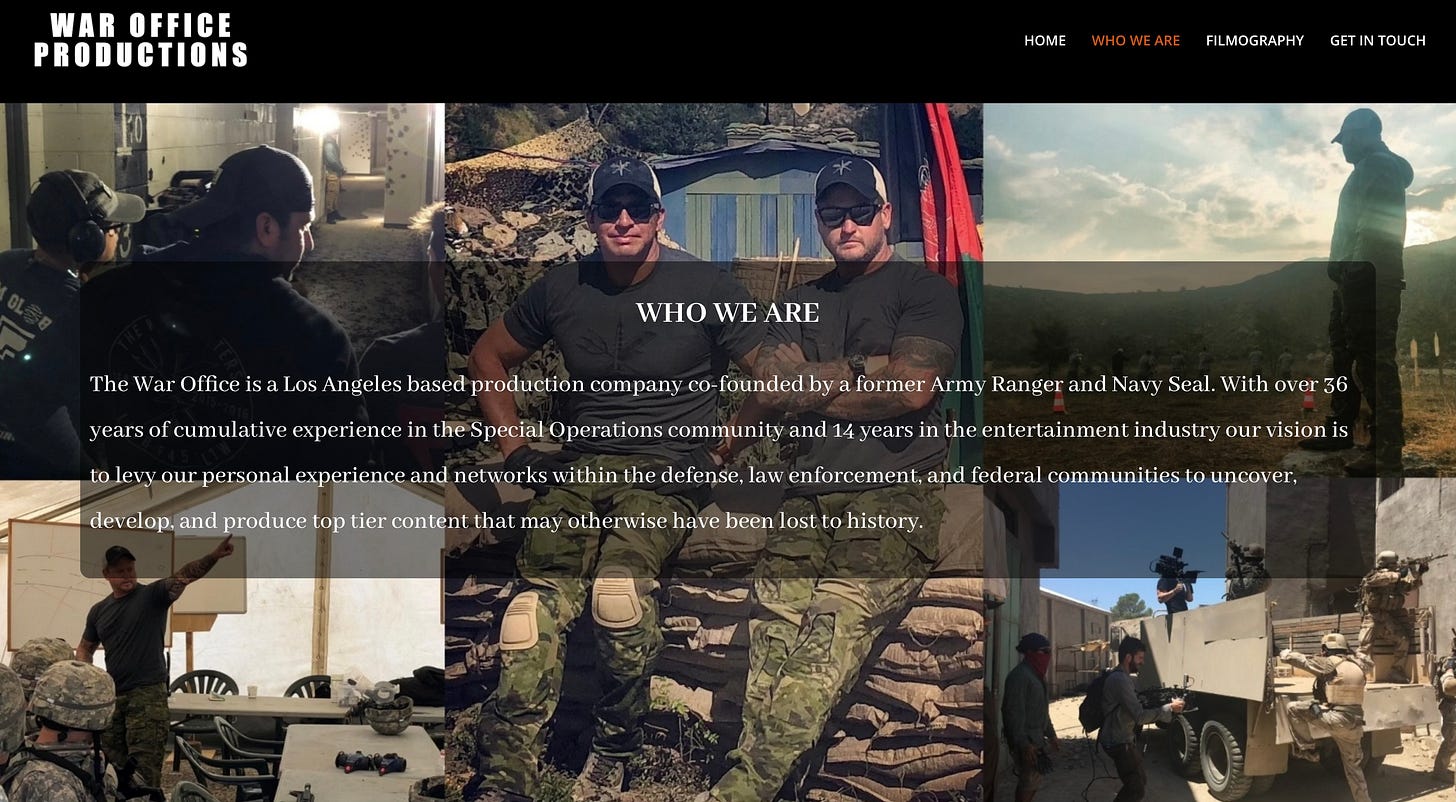

At best this sequence faintly misguided, at worst it undermines every single second of the film. Imagine if The Zone of Interest ended with a featurette on how they designed the house and you’ve got a pretty clear idea of how strangely it plays: it feels icky, insidious even, downright evil. I don’t know what they were thinking. If we give them the benefit of the doubt it’s merely a spectacular misjudgement. But then you visit the website for Mendoza’s production company, the aptly-named WAR OFFICE PRODUCTIONS, and suddenly it all clicks into place:

What you’ve been watching is sheer propaganda, manufactured with the explicit support of the Army and Navy, using their assets, using their branding. Warfare is agitprop repackaged for our era of prestige filmmaking. Quite why A24 got behind this is a mystery to me. But, if I’m being totally honest, I don’t actually think there’s anything necessarily wrong with the fact they did. The era of political neutrality is done and dusted. From the BBC news to Grey’s Anatomy, everybody is trying to sell something. At least Warfare is obvious, which actually makes it quite sweet. It’s like a clumsy dog vying for your affections. “Who’s a good boy?!” etc. Most people will be able to pick up on what angle this is working from pretty easily. Unlike Netflix’s dismal Adolescence, which is downright evil in how brazenly it repurposes hot-button topics to shamefully manipulate its audience, I don’t think Warfare originated from a place of malignancy: quite the opposite, in fact.

The best thing I can say about Warfare - awful credits included - is that it feels very earnest, if misguided. I think that Ray Mendoza is a veteran of war, and I think that Alex Garland is a director who clearly wanted to help him realise his vision of how we could depict that war on screen, to pull the narrative focus away from the suits at the top, to the normal people fighting on the ground. I just wish that it didn’t feel so empty. I can see every second of it, but I feel absolutely none of it. And I think about that drone footage. The camera pulling back, further and further so that the men appear smaller and smaller, clouds appearing now and making the footage even hazier, more blurred. And now these scared, little boys playing with their toys are enveloped by their surroundings, vanished completely. It’s like they were never there to begin with.a

Warfare releases in UK cinemas 18 April 2025.

If you liked this, you can follow me on Letterboxd here.